Higher than expected inflation dynamics in 2021

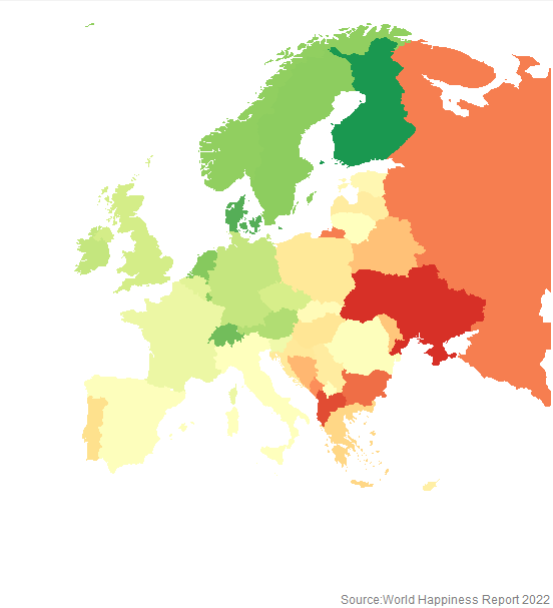

It is shortly before two years since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the shockwave induced by the emergence of the pandemic continues to propagate globally, negatively affecting both economic activity and social life. A hot topic of discussion this year is the large rise in commodity prices and the high inflation rates observed in many economies. In September, annual inflation was 5.4% in the US and 3.4% in the euro area (4.1% in Germany and 2.7% in France). Inflationary pressures are quite high in Central and Eastern Europe, with the annual inflation rate reaching 5.9% in Poland in September, 5.5% in Hungary and 4.9% in the Czech Republic. The annual inflation rate in Romania reached 6.3% in September.

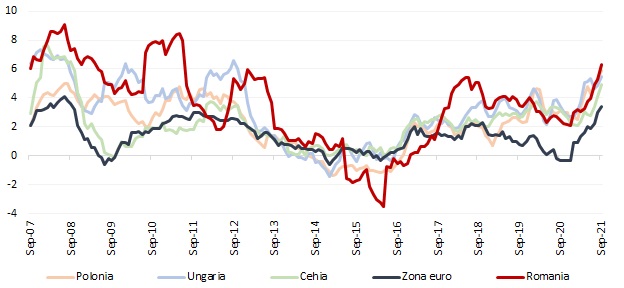

Inflation dynamics in the euro area and Central and Eastern Europe

Source: National statistical institutes

Rapid growth in consumer prices is substantially eroding the purchasing power of the population, jeopardising the process of economic recovery and social stability (especially in poor countries). Also, the persistence of the inflation rate at a very high level for a longer period of time may cause an increase in the inflationary expectations of population and companies, sowing its seed an inflationary spiral. However, central banks are not very worried about the high levels of inflation rates seen this year, considering them to be transitory in nature. Specifically, these high inflation rates would be the expression of an inflationary crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and whose duration should be relatively short. Central banks forecast the return of inflation to low levels in 2022, close to their inflation targets. Thus, the US central bank (Fed) and the European Central Bank have not rushed to respond to the rapid rise in the rate of inflation by increasing the restriction of monetary policy. However, the situation has been different in emerging economies where, due to the much faster increase in inflation rates and the lower credibility of central banks in managing the inflationary process, central banks have begun to raise policy interest rates. In this case, too, it is a question of a “normalization” of the character of monetary policy, the increase in interest rates materializing from very low levels. In Central and Eastern Europe, policy interest rates have been raised this year in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Causes of the inflationary spike in 2021

The rapid increase in the prices of consumer goods and services observed this year in many developed and developing economies is the consequence of the simultaneous materialization of an accumulation of factors with an inflationary effect.

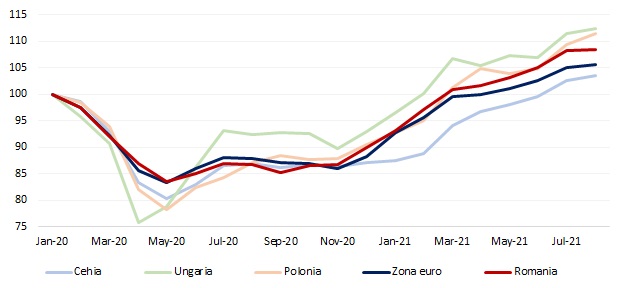

Thus, the basis of comparison, namely the price level of 2020, is low. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of economies have led to large decreases for many categories of prices and tariffs, especially in developed countries. In this case, the ample decreases in the prices of petrol and diesel, air transport tickets and hotel accommodation rates are easily noticed. The vat decrease in Germany during the last 6 months of 2020 has acted in the same direction (lower prices). In 2021, amid the reopening of economies as a result of the advance of the vaccination process, prices that have fallen in 2020 are rising, returning to levels existing before the onset of the pandemic. For several categories of goods and services, the large price increases observed in 2021 compensate for the decreases materialized in 2020 and are not an expression of a permanent acceleration of the growth rate.

Evolution of the price of petrol and diesel (fixed base indices, January 2020 =100)

The materialization of the COVID-19 pandemic has produced substantial changes in the structure of consumer demand. The prompt and large-scale intervention of governments and central banks through money transfers to population and companies has preserved their purchasing power and financial situation. The imposition of restrictions to limit the spread of the pandemic has led to a large decrease in the consumption of services (severe limitation especially of the consumption of services based on intense social contact). As a result, the population has allocated a much larger part of the disposable income maintained at a high level to the payment of goods (especially for goods intended to increase the comfort of living). Thus, the substantial re-demand for certain categories of goods has generated pressures to increase the prices of these goods.

The materialization of the COVID-19 pandemic has produced major bottlenecks in the chains of production and distribution of goods in global trade. The bottlenecks were favoured by structural changes induced to the demand of households and companies (increasing purchases of durable goods) and by the way global production and distribution chains are organized (high concentration of goods production in Asia, especially in China; use of the just-in-time system for organizing production and distribution). The materialization of the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially increased the demand for goods made in highly concentrated production capacities (in Asia) and has affected the development of the activity of production and delivery of goods carried out in these production capacities (episodes of suspension of activity in order to limit the spread of the virus). The crisis of semiconductors and electronic components, the congestion of the shipping routes of the goods made and the lack of containers for maritime transport are the expression of the bottlenecks in the global production and distribution chains. The inability of supply to rise and accommodate the growing demand for certain consumer goods has supported the rise in the prices of these goods.

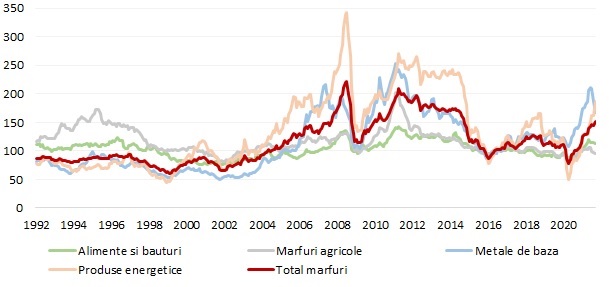

Evolution of commodity prices (fixed-based indices, 2016=100)

Note: levels deflated with the US Consumer Price Index; last observation is for September 2021

Source: International Monetary Fund, author’s computations

The most visible price increase materialized during the last year remains the one observed in the case of raw materials, both those with energy character (oil, natural gas, coal) and those of non-energy character (base metals, agricultural products, food goods). According to the aggregate commodity price index calculated by the IMF, they increased by 59.5% over the last 12 months (from September 2020 to September 2021). Between September 2020 and September 2021, the prices of energy-related raw materials increased by 136% (+78% for the oil price, +355% for the price of natural gas, +218% for the price of coal). In the same period, the prices of base metals increased by 26%, the prices of raw agricultural products increased by 12.4% and the prices of food and beverages increased by 29%. The increases in the prices of raw materials observed in the last 12 months far exceed the decreases in 2020, the level in September this year being in all cases substantially above that recorded before the onset of the pandemic (in December 2019). Thus, the aggregate commodity price index calculated by the IMF increased by 43.8% from December 2019 to September 2021. The very rapid increase in commodity prices in the latter has been favored by several factors: their low level in2020; the rapid recovery of demand and the prospects of a robust global economic growth materializing in the coming years, including against the background of the investment programs in the US and the Union European; the lack of investment in new production capacities during the last few years that has limited the growth of supply; the process of transition to a green economy that favours the ample increase in demand for certain raw materials not only in the long term, but also in the short term; geopolitical factors (the management of oil supply by O PEC, management of natural gas production and distribution by Russia); materialization of adverse events (hurricanes, floods, drought); transactions to ensure the protection of investors against rising inflation and speculative transactions.

Controlling the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has required the increase of the technical and sanitary security norms, generating an increase in the costs of carrying out some activities that have been translated into increases in prices and tariffs paid by final consumers as there has been an increase in consumer demand.

Prospect of a return to low inflation rates

Most of the factors mentioned above as causes of the 2021 inflationary spike should be temporary in nature, even though they continued to manifest themselves for a longer period of time than initially expected (e.g. bottlenecks in global production and distribution chains) and have generated unexpectedly large price increases (especially the rise in energy prices). The expected normalisation of the production and distribution processes and the increase in the supply of goods should limit the price increase in the coming period.

At the same time, there are expectations that the factors that kept the inflation rate at an unexpectedly low level before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to act. Thus, the increase in the prices of consumer goods and services could be further limited by automation, digitalisation, globalisation and the aging process of the population. A low medium- to long-term path of persistent inflationary pressures will allow inflation to remain low in the short term if adverse supply shocks continue to occur, provided, however, that their magnitude is not very large.

Risks to perpetuating higher inflation rates

There is a possibility that the bottlenecks in the global production and distribution chains will be prolonged further, including in 2022, supporting a faster price advance than currently expected, as consumer demand from the population remains high.

Even though commodity prices have risen substantially over the last year, their current level is not very high from a historical perspective. If expectations of continued global growth at a sustained pace in the coming period are confirmed and if the transition to the green economy accelerates, then a significant part of the increase in commodity prices observed over the past year could be permanent. In this scenario, the very large increases in commodity prices observed in 2021 should gradually translate into increases in the prices of consumer goods and services in 2022 and beyond.

Keeping the inflation rate at a very high level or visibly higher than that seen in the decade leading up to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic for a longer period of time could lead to an increase in public inflationary expectations to a higher level than that desired by central banks.

Although the last 13 years have not revealed any link between the ample volume of liquidity injected by central banks into the economy and the evolution of inflation, it cannot be completely excluded that the extension of the period during which central banks keep the monetary policy very accommodative will lead to a visible increase in the rate of inflation. This could be favoured by the high level of public budget deficits.